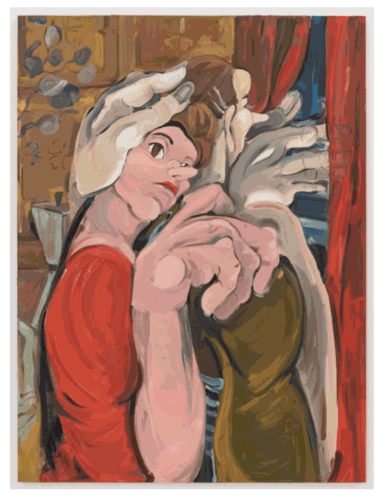

Cristina BanBan’s Del Llanto is the perfect answer to the tedious, inevitable question, “And what have you been doing during the pandemic?” She’s been mighty busy, so much so that she’s filled two venues, 1969 Gallery in Tribeca and albertz benda in Chelsea, with her efforts: over 30 works in oil, acrylic, pastel, and charcoal. But she has not only produced: she has evolved. Confinement for BanBan has worked like forcing flowers in a hothouse. She has left behind her previous caricature or cartoon style and blossomed into an early maturity. In Spanish, we might say she has achieved “plenos poderes” (full powers). The collective title of this double show is Del Llanto, which might be translated as “concerning weeping,” in the sense of an essay on or an interpretation of tears and their consequences, grief in particular. But in Cristina BanBan’s Spanish culture the word “llanto” transcends tears. In 1935, Federico García Lorca published his poem “Llanto por la muerte de Ignacio Sánchez Mejías,” about the death of a bullfighter, so “llanto” can entail elegy or lamentation as well as crying. In BanBan’s case, both meanings hold true: the tears shed during this year of pandemic loss and the elegiac, commemorative mood that prevails in all our lives.

So being acquainted with grief, following Freud, opens two paths: mourning and melancholia. Mourning we overcome; melancholia is a pathological condition, one that afflicts the distracted, abstracted women who populate BanBan’s paintings. This entire body of work might best be construed as an exercise in sublimation, not in Freud’s sense of the transmutation of erotic energy into art but in the translation of felt grief into images of grief.

The works hung in the albertz benda space show BanBan moving in new directions. Yes, we still have her large-handed women lounging in a daze on beds, but we also have a new preoccupation with the artist’s studio. Art about art emerges here as a major subject.