It is said in West Africa that nothing measures your success better than the number of envious people. And if envy may be one of the biggest obstacles to social progress in Mali, then Famakan Magassa can at least be sure that he made it. “I often have to listen to harsh words at exhibitions in Bamako,” says the 24-year-old painter and shooting star of the art scene. “Mostly they come from older artist colleagues. They tell me: Your art has no meaning. Or: Come to my studio and I’ll show you how to paint properly.”

Older people are not so easily contradicted in Mali. So anyone with a few gray hair on their head can step past everyone else to the counter, even if a queue has been formed there for hours. How does he react then? Magassa, a lanky guy with glasses and a curious look, lifts up a paperback book. Marshall B. Rosenberg’s “Nonviolent Communication” in the French translation. “I want to assess the situation correctly, analyze it and then react appropriately.”

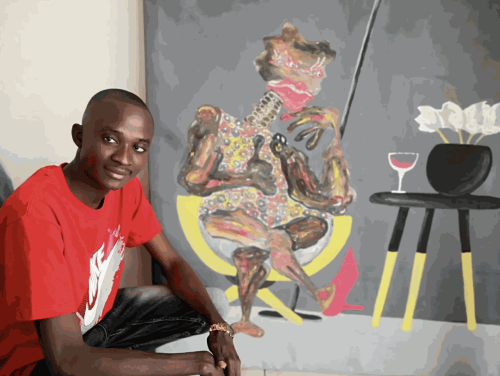

Magassa gives you a disarming smile. Then he puts the book back on the glass table in the apartment of a Dutch art collector in a business district in Bamako. In the absence of a studio, he only has this place to present his work appropriately. One of his large-format acrylic paintings hangs on the wall. Magassa sold the rest of his work to European collectors last year or the pictures hang in galleries across the Atlantic. For a few months now he has had an international agent: the Albertz Benda Gallery in New York.

“I belong to the whole world. And it belongs to me.”

Magassa is the youngest represented artist there. And the only African. This is – for the gallery – to be understood as a strategy for the future, contemporary art from Africa is currently in fashion between Paris, New York and Berlin. Galleries specializing in the marketing of young African artists are opening up, especially in Europe. “But what happens when this wave is over?” Asks Magassa. “I don’t want to be perceived as an African alone, nor as an African artist, but as an artist. I belong to the whole world. And they belong to me.”

“From daycare to New York.” This was the headline of a Malian newspaper about the young painter’s rapid rise. Kita is a small town in western Mali and Magassa’s birthplace. As a child he would walk around here with pen in hand. Magassa was therefore responsible for the blackboard painting at school: in biology class he drew plants and animals, and in geography entire maps. Later, when he came to Bamako for his A-levels and studies at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers Multimédia, the teenager used his talent to earn money: “I painted shop signs, designed banderoles, T-shirts and advertising posters. But above all I made portraits . ” Magassa swipes his smartphone and presents one of his early works. A pretty photo-realistic portrait of an elderly white woman. “In Bamako I regularly visited the artists’ commune Ateliers Badialan and Amadou Sanogo, one of our most famous painters. He always said to me: Stop painting portraits and look for something of your own.”

Magassa found what he was looking for at a cultural festival in the small town of Segou, about 200 kilometers north on the banks of the Niger. He saw men in women’s clothes and vice versa, adults riding wooden horses or dancing in circles with bizarre glasses and hats. The Koredugaw. He had never heard of this Bambara secret society before. His social function fascinated him even more than the spectacle: “They think differently from the others and do what they want. This unlimited freedom of expression appealed to me immediately.” The fact that the Koredugaw break all conventions of everyday life is not an end in itself. No, says Magassa, “they use humor to resolve social conflicts. Their goal is peaceful coexistence in society”.

In a comic-like manner, the young painter turns the urges of his figure outwards

Since then, the Koredugaw have mastered Magassa’s canvases. They inspire his deformed human body, whose facial parts and limbs often seem to lead a life of their own. Magassa points to the large-format painting on the wall opposite: wide eyes, greedy lip bulges, shapeless hands. The female figure is sitting on a modern lounge chair, legs crossed, a glass of wine next to her. In a comic-like manner, the young painter turns his character’s instinctual life outwards – until it appears like a zombie hungry for life.

Magassa’s paintings could be classified somewhere between Brueghel, Dubuffet and Basquiat if they did not come from a very special animistic-African context. The Koredugaw are always tricksters, way openers who mediate between divine wisdom and human madness. Magassa’s material fits in with their idea of recycling everything: He paints with wall paint that is commonly used to paint house walls in Bamako. Once he also tried expensive imported paints from Abidjan – but was dissatisfied with the result.

How does a young artist market himself in an environment where there are hardly any museums or galleries?

All the more he invests in the concept of his art. His series, he says, are “strictly formatted”. He reads books on psychology, sociology and art history, and when he has found a topic, he first writes a text. Then he determines how many pictures the series should consist of. “I think of a title for each picture in advance – only when all of this is in place does the actual painting begin for me.”

And how does a young artist market himself when he comes from a country like Mali? What if there are hardly any museums or galleries in his environment – as in most of Africa? He knows enough rich people in Mali, says Magassa. But there is no art market. “It’s a question of education. Most people would rather buy a third car than a work of art.”

The young painter smiles. He had his first exhibition in 2019 at the Institut français in Bamako. You have suddenly given him contacts in Europe. Contacts that should change everything for him – thanks to his communication strategy. “Many of my colleagues here are just waiting for a buyer to discover them via Facebook or Instagram. But I actively write to people who I think are potential buyers. Those who reply, I regularly send messages and pictures of my latest work. It doesn’t matter if he ever buys something or not. ” So he created a network of supporters.

It was European collectors who Magassa organized several exhibitions in Paris in 2020. They also paved the way for him to New York. Magassa had previously completed a three-month residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris together with his sculptor colleague Ibrahim Kébé – the two are founders of the Sanou’Art artist collective in Bamako. Magassa expanded his subject there: he called his new series “Soif”, thirst. The figures were based on his Koredugaw series, but now they symbolized human greed with open mouths and demanding gestures. “I want,” says Magassa, “to represent the insatiable desire for pleasure, power, love, lust and appreciation. A person can never be satisfied. He always finds something that he lacks.”

Magassa has now sent all of the 21 canvases in the “Soif” series to the Albertz Benda Gallery in New York. The topic has universal appeal, especially in times of the renunciation of the environment and social peace: Mali, says Magassa, is one of the poorest countries in the world. But the people there cherished the same dreams as Europeans or Americans – only the means to fulfill these wishes were unfairly distributed. Magassa’s very own wish, however, has nothing to do with fame or money: “I hope I never have to hear again that I should learn to paint first.”