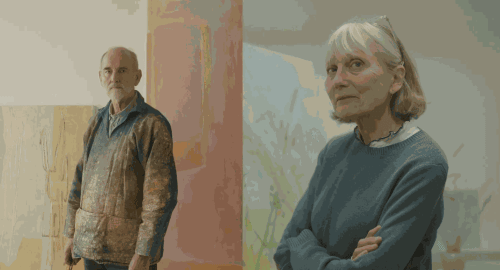

Your exhibition ‘Left Hand, Right Hand’ at The Gallery at Windsor marks a significant collaboration, the first time you’ve shown your paintings together. Could I ask why now? What was the inspiration behind this joint venture?

Charlotte Verity: Mysteriously, when the offer came, the timing felt right. The work might have appeared too divergent at earlier points in our career, but now it felt not only possible to make a show with some coherence, but an interesting one – not least, for ourselves.

Having guarded our independence hitherto, we were curious to see what the paintings would look like side by side and prepared to take a risk. The unpredictable element was exciting. But when finally the paintings were in place, the show felt settled and harmonious. There was more in common than we had realised.

On the other hand it felt good to present an exhibition where the wide scope of painting could be enjoyed, and how the same materials – paint on canvas – can achieve such a variety of things in different hands.

The title speaks to a commonality as well as a difference. What are the ways your work complements each other, and what are the ways it contrasts?

CV: Our differences were evident from the beginning. At The Slade, we each gravitated towards areas of the school under tutors whose work and outlook were in great contrast to each other. Naturally, this period was formative. However, we were both drawn to painting at a time when the value of making paintings itself was being fiercely challenged. If we had wanted to we could have engaged with conceptual and performance art, sculpture or photography and film – all at a high level. Painters had to fight their corner. Our work had to be strong and forward looking if it was to be noticed and taken seriously. However within the field of painting, of course – an artist must work with their temperament (anything else would be academic) and this is always unique so it follows that our work has developed along different lines.

My imagination, in the sense that Coleridge defined it, is stimulated by the world around me.

The circumstances in which we work are not similar. I like to work in silence, paying close attention to what I see. As well as larger areas of brushed on colour I use the point of the brush almost as an extension of my eye, whereas Christopher’s approach to drawing is more gestural, especially in this recent phase. He makes marks in any way he can, always inventing, and pushing his handling in different directions in order to achieve a painting with its own life. For me this is also an important criteria but the elements that make up the finished work are observed moments manifested by corresponding brush marks. My imagination, in the sense that Coleridge defined it, is stimulated by the world around me.

Christopher’s paintings are built up by covering the canvas, layer upon layer until something utterly new is formed, whereas my tendency is to coax the painting into being over time until, together with engagement with the natural world, it becomes an independent painting. A sculptor would distinguish the two approaches as modelling and carving respectively.

I wanted to ask about poetry. You mentioned both T. S. Eliot and Philip Larkin as poets you admire, both of whom we have published in The London Magazine. How does their poetry, or poetry in general, map onto your creative processes?

Christopher Le Brun: I’ve always wanted to record and pay tribute to the authors and books that have been important to me, but I could never before quite see how to do it, until I realised that it should be a painting rather than just a list. Bibliography is the last painting reproduced in the book on my work of the last decade being published by Rizzoli this September. For someone of my background it is inevitable that Eliot and Larkin should be included, but I tried to make it truthful and comprehensive by including those I had read as a child and teenager.

Whenever I plan and imagine work away from the studio, I find that it’s the images that occur while reading that have most resonance. In fact, it often happens more intensely through the written word or in listening to music than through direct visual experience. You mentioned Larkin and Eliot, and Larkin would probably have been rather contemptuous of this as it doesn’t reach the threshold for art of experienced reality, but I would have expected Eliot to understand, given his concept of the cultural imagination. I don’t question these intuitive prompts, instead I submit to them and seek them out. The images I envision aren’t descriptive, they are more like symbols, atmospheres and parallels. It may explain why my first encounters with authors such as Virginia Woolf, Edward Thomas and David Gascoyne were so formative.

CV: The poets I have come across and re-read, give me courage to work in the way I do. The language itself is re-invented in order to move from describing, or even reporting – with an extraordinary precision – through to the expression of both thoughts and feelings of a profound and elusive nature. I find reassurance in this aspect of poetry which in its turn, gives me a freedom to go to a level of precision without limiting the ability of the painting to have a more universal significance.

Eliot and Larkin resonate in different ways, and there are many others who are fundamental to my feeling for art. My reading of John Clare’s Nest poems is an example of the above. Reading Clare, I almost identify with the boy who, having a sense (carefully developed by him during the few years of his boyhood) that a bird’s nest is nearby, he finds his way through an almost impenetrable thicket to find it. Once there, he is very moved by what he finds despite knowing what to expect. His description is tender and respectful of his subject, his writing is full of wonder and curiosity. It is very precise about what he sees, but also about the search. Even so, as readers, we know that his is not just about the bird nesting. What he describes is how it feels to make a painting. At the heart of it is the search for and expression of something precious and fragile, guarded and hard to find. But if approached in the same speculative way, a form accrues which becomes whole, complete and with its own sort of strength.

My Nest was painted outside in winter looking towards the boundary of our home which was made up of a tangled mass of thorny stems above the garden wall. This perhaps, is the most obvious link to poetry in this group of work, but the insights, held within many other poems by a range of authors, resonate as I work. They set a standard – a very high one!

While you share a mutual preoccupation with nature, your approaches differ: abstraction versus specificity, or figuration versus still life. How are these differing methodologies in dialogue within the shared exhibition?

CLB: Nature’s there, but through painted means, through light and space and colour, atmosphere and distance. It’s true that we use different methods or approaches such as, say, close observation versus imagination but there are shared values too. For example, there is a reluctance to overprescribe, preferring to invite the viewer, rather than coerce them. I don’t believe either of us works without (in the metaphorical sense of the word) a certain distancing and Charlotte is careful to approach content obliquely.

I find it almost impossible to look at a painting without thinking how it’s made.

Howsoever you describe it, subject matter or content are difficult things for a painter. Painting’s presence is resistant and self-sufficient. It is therefore an unwilling message carrier, as using it for illustration’s sake will betray it. I would like to say that we are both more in favour of speaking rather than shouting, and as visual hunters we are happier when seeking than we are when parading the spoils of the hunt. Although I may have given the game away here as I do have an occasional inclination for parading.

The concept of time and seasonal change appears prevalent in your recent works. How do you each interpret and convey the passage of time in your art?

CLB: I find it almost impossible to look at a painting without thinking how it’s made – whether it’s in the repeated dots of Seurat, or the looping splashes of Pollock. Painting works not just through the eye but through physical sympathy, so as you discover the painting, you are also led through the sequence of building this structure over time, piece by piece. Painting is less about an idea or conveying a message, than engaging in a mysterious process. Time plays a central role in the experience of painting both for the viewer and the painter. The seasons become a way of symbolising that.

I interviewed artist Rose Electra Harris recently, who described her increasingly abstract style as ‘more freeing’, and able to capture the scattered nature of her mind more accurately. Christopher, can I ask how you feel about abstraction? Why is that often the medium or style you turn to?

CLB: Abstraction is a language that we associate with the idea of modern art. New techniques and combinations of colour, line and scale never seen before, continue to emerge even after a century of development. That’s an enticing prospect – it’s the promise of the field of snow without a footprint. Not so long ago, identifying as an abstract artist showed loyalty to modernism. But that phase has passed, and I feel now that being described as abstract or figurative is false – it’s really not like that. Resemblance is a better measure, and it occurs on a very wide range from full recognisability, something we can name and agree on, to something unrecognisable and nameless. This doesn’t mean that it is generalised, in fact it’s even more important to be specific. My work has led me this way recently but I know from the cycles of my past work that there will be other changes which I can’t foresee.

Edmund de Waal, in his piece on you, Christopher, asked a series of questions about decisions. ‘When is a painting finished? Do you hover over it, or is it, as Auden said of a poem, “never finished, only abandoned”? How about the title? Is it finished when the name, the luggage label, is put round its neck and it is moved towards the door? Is it finished on the gallery wall?’ As a point to end, can I put the same questions to you – when is a painting, any work of art, finished?

CLB: The trope in the West that claims art is deathless and defies time presumes that a moment finally arrives that is somehow different at that point from all the other decisions and states of mind that preceded it. In my experience it is never that clear. In the studio the rule of continuous and ruthless change governs everything right up until the very moment that the painting leaves. That doesn’t mean that it’s not sent off without the necessary conviction, it’s more like something organic, becoming ripe and ready for harvest over hours or days rather than in one special moment. As for the titles, they either lead a lonely life, lingering for many years before finding the right partner, or come as if from nowhere all of a sudden. I wonder whether the subsequent display in the quasi-perfection of the gallery is meant to suggest a sort of heaven, way above the messy contingency of the studio or the compromises of daily life. This should reassure us that yes, it is finally, and unarguably, complete.